Who Are Our Students? Language and contextual information

Click here to hear this blog post read in Jess’ voice.

If you’ve found this blog post, you’ve probably at least glanced at other parts of our website or social media where we talk about “students with high support needs.” This entry is meant to not only clarify that term, but also explain why we use that language instead of any of the other options to describe our students. Our word choices are not our own original ideas, but have been adopted from listening to other members of the disability community about their preferences and insights on language regarding their lives and how language impacts them.

With the exception of some inclusion preschool classes that include typically-developing peers, all of our students are disabled. Disability is not a bad word. For many people, being disabled is part of their identity and they hate having it minimized or erased. This is true for members of our own Medley team who identify as neurodivergent or otherwise disabled.

Many people still use the euphemism “special needs” to avoid discussing disability. While this is considered polite in some circles, those social groups tend to perceive disability as a negative thing. We at Medley don’t. Disability is a fact of life and part of our natural human diversity. It is not something shameful, it is not a moral failing or character flaw, and it deserves recognition, support and intentional inclusion. Standing up for disability justice is a moral imperative in our book.

So yes, our students are disabled. And they are perfect exactly as they are. They are growing and developing like all children do. While we do teach some inclusion preschool classes as previously mentioned, the greater part of our adaptive music lessons are delivered in sub-separate Special Education classrooms in the public schools.

A majority of our students are autistic. We don’t say that they have Autism Spectrum Disorder because we believe that neurodivergence is a difference and not a disorder or deficit. We don’t often describe our students as being ‘on the spectrum’ because that minimizes autism as part of their identity. Autism is not an accessory; it is in the wiring of the brain and it filters how you perceive and express yourself in the world. It cannot be separated from the person. Language that suggests otherwise implies that autism should be obscured or understood to be shameful in some way. We will insistently refer to individuals with this neurotype as simply autistic.

The population in our autism program includes many children who are nonspeaking or minimally speaking. We do not use the term ‘nonverbal’ because it is inaccurate in so many cases. Your verbal skills include not only your ability to speak but also to understand spoken speech and to read and write. Most disabled people who don’t speak still understand much or all of the language around them, and many will express themselves very eloquently with the appropriate communication tools. Particularly with autists, the inability to speak is more or less a motor impairment; it is a complex process to coordinate the breath, lips, tongue, jaw, and vocal mechanism to form words. Of course some people with neurodivergence struggle with this particular skill! It doesn’t mean that they don’t understand language. So if you refer to a nonspeaker as nonverbal, you are likely assigning deficits to them that don’t exist, and that will negatively impact the quality of support that you offer them.

Many of our students also have intellectual disabilities, which means that their capacity for learning is well below average. Intellectual and developmental disabilities occur in approximately thirty percent of autistic individuals, but not all of our autistic students are intellectually disabled, nor are all our intellectually disabled students autistic.

Some of the sub-separate classes we teach are not for autistic children but instead for those with complex medical needs and intellectual disabilities. There is always a nurse on duty in these classrooms to help with breathing tubes, G-tubes for feeding, potential seizures and more. Almost all are nonspeaking. Some are blind and/or deaf. As a group they have a range of motor control. Some are able to cause mischief by unpacking our bags and throwing things on the floor (which we playfully protest but often allow because their cackles are such a delight). Others have little to no willful control of their arms but turn their heads and use their faces expressively. Over the years, we’ve had a few students whom we rarely or never observed turning their heads or outwardly responding to stimuli. We do not know what their internal experience is like so we just assume that they appreciate loving, playful musical interactions the same as any other child. We support them in taking as many turns as their peers even though it may not look like they are participating. There is never a downside to treating children with dignity and warmth, but there is great value for the entire classroom community in doing so, and hopefully also for these students in particular.

You may notice that one common phrase is missing in this description of our most vulnerable students: we do not ever use the terms “high functioning” and “low functioning.” These terms compare humans to appliances in a dehumanizing way, but more importantly, they totally lack understanding of the complexity of disability. Any person’s abilities can vary from day to day and minute to minute, and the extent of this phenomenon– known as fluctuating capacity– tends to be more extreme among disabled people than the general population. Even without variation over time, neurodivergent people also tend to have spiky profiles, which means the distance between their strengths and weaknesses is unusually wide compared to non-disabled people. Some easily observed spiky profiles among our students include children who are prodigious engineers but struggle with self regulation, have limited speech but perfect pitch and related musical sensitivity, or are highly verbal but struggle with the demands of social interaction in the classroom. In these cases, broad ‘functioning’ labels are painfully unspecific. The term is too blunt to be useful.

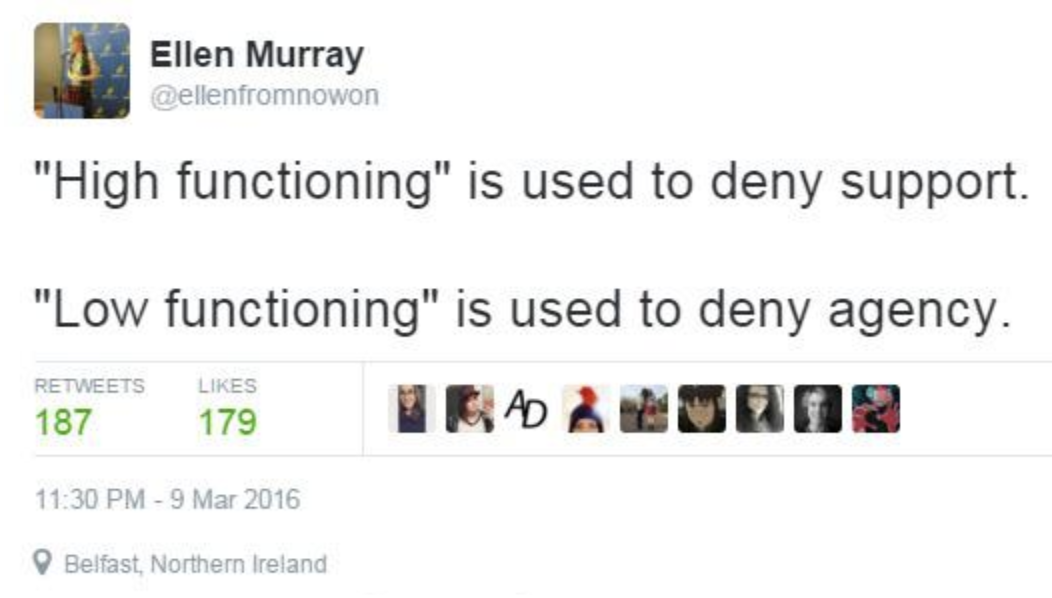

Perhaps the greatest problem with functioning labels is that they make listeners jump to conclusions about the needs and abilities of the described person. When one hears “low functioning” they assume consistently low abilities, anticipate a lack of independence, and interact with that person accordingly. When one hears “high functioning” they assume support is not needed and may leave that individual struggling underneath their masking. As Ellen Murray says succinctly: “High functioning” is used to deny support. “Low functioning” is used to deny agency.

We understand what well-intentioned people mean to convey when they use functioning terms. The disability-affirming alternative is to describe an individual’s level of support needs. It makes no false claims about overall ability levels and instead focuses on the fact that the subject will be successful when given the appropriate level of support.

Medley’s materials focus on students with high support needs for the simple reason that most music teachers already have some level of comfort working with students with lower support needs. In reality, we work with and love learners of all levels of support needs, and we have advice and strategies that support the growth of all learners. Check out our upcoming professional development schedule for opportunities to explore these topics with us.